A Counting Crows (By Me) Reader

Looking Back On 30+ Years Of Writing About The Greatest Multi-Platinum Folk-Rock Band Of The '90s, In Conjunction With A New Documentary

Thank you to all the people who have subscribed since this newsletter switched over to paid last week. The response has been phenomenal. As I type this we are currently the No. 1 “Rising” music newsletter on Substack. Expect more regular programming after the holidays, including the debut of the new “Catalog Club” feature. For now, please enjoy this free post!

A few weeks ago, one of the editors I work with at The Ringer asked if I wanted to write something about Counting Crows in conjunction with the new documentary the company produced for HBO. My response was complicated. On one hand, I like money. Plus, I love writing about Counting Crows, a ’90s alt-rock band whose story and legacy explains a lot about the meaning and history of ’90s alt-rock. On the other hand, I have already written a lot about Counting Crows. There is no way to definitively quantify this, but I would guess that I have written about this band more than all but .001 percent of gainfully employed music critics. In terms of Adam Duritz-related thinkpieces, the leaderboard includes me and possibly some unknown lunatic who is presently the subject of a restraining order filed by Adam Duritz.

But again: I like money. So I asked myself: What more do I possibly have to say about this band? Actually: Plenty, I decided. The resulting article is my longest and most comprehensive essay on the Crows. (Do I dare add “yet” to that sentence?)

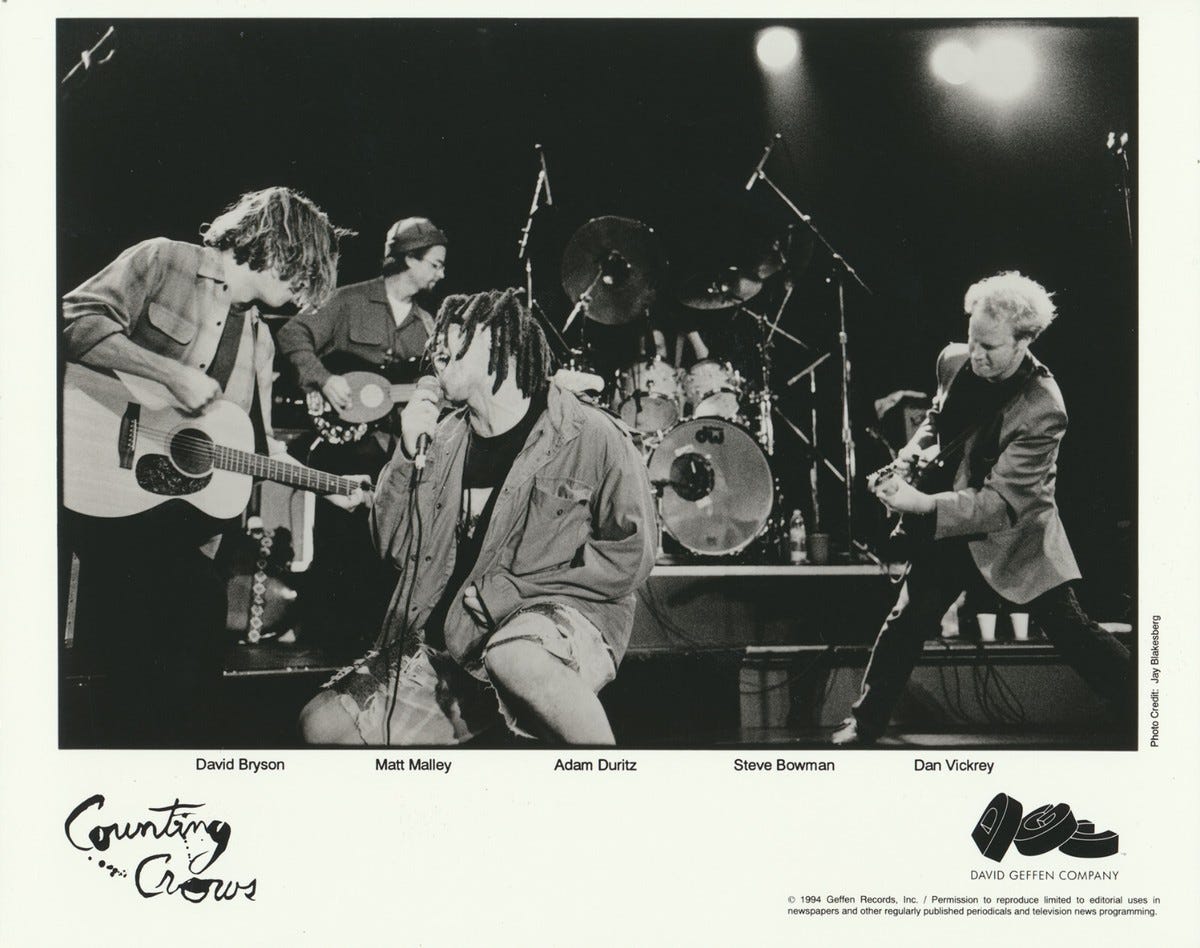

The paradox of Counting Crows—this is true of most ’90s rock bands who aren’t Nirvana or Radiohead—is that everybody knows who they are but is aware of only one or two of their songs. And often not by the titles, just the most quoted lyrics. For the Crows, those tunes are “Mr. Jones” (the “I wanna be Bob Dylan” song) and “A Long December” (the one where the guy hopes that “maybe this year will be better than the last”). As noted in Counting Crows: Have You Seen Me Lately?—which was coproduced by Ringer Films as part of HBO’s Music Box series—they are also remembered for two extremely ’90s pop culture artifacts, which for years provided fodder for uncreative stand-up comics and late-night talk show hosts: Duritz’s uniquely public dating history (highlighted by dalliances with two Friends cast members) and his distinctive dreadlocks, which made him infinitely more recognizable (not necessarily in a good way) than the typical tortured poet in MTV’s Buzz Bin. Duritz’s hair even gets its own narrative arc in the film, with a distinct beginning (his abrupt embrace of locks initially shocked the other band members), middle (SNL made some cruel/lame jokes), and conclusion (his girlfriend gently persuaded him to pivot in middle age).

Otherwise, director Amy Scott stays focused on their first two albums, 1993’s seven-times-platinum debut, August and Everything After, and the not-quite-as-successful follow-up from 1996, Recovering the Satellites. For a film aimed at a general-interest audience, this approach is smart and logical—the aforementioned songs, for one, derive from those records—even though those albums account for only 25 percent of their studio output. Nevertheless, I’ve been troubled by my own paradox (or maybe it’s just a minor inconvenience): I am a working rock critic whose extensive knowledge of “deep-cut” Counting Crows LPs has been professionally useless to me. For years, I have been prepared to impart observations about how the “loud” Side 1 of 2008’s Saturday Nights & Sunday Mornings informs the “quiet” Side 2. But I have had nowhere to put that information.

That last sentence is a lie. Like I said, I’ve put my “useless” Counting Crows “information” in plenty of places. I have, in fact, done it going back over 30 (!) years. Even more incredible is that I’ve had enough to say to justify all those pieces, including this new one that goes on (sorry, breezes by) for just over 4,000 words. I happen to think the Ringer piece is the pièce de résistance of my personal Counting Crows canon. My own “Round Here,” to put it in Duritz-speak.

But I do like the other pieces I’ve written, too. Well, most of them, anyway. Not this one so much. It’s the oldest one, from way way back in 1994. I’m including it for posterity.

I was 16 years old, a teen columnist for my hometown paper. (I have shared other articles from this era in this newsletter.) It was a review of August And Everything After, which I gave an “A” and called “possibly the best album released last year.”

They have a sound that many critics have likened to The Band, Van Morrison, and R.E.M., which is pretty good company to be in. The Crows have a folk-based sound, but they flavor it with touches of rock, country, and blues. The results are warm, intimate sounds that remind one of the past but definitely points forward into new, musical directions.

August And Everything After blends the ensemble playing of Counting Crows into a lovely mixture. No one player dominates this band. Instead they create music that manages to display their talents without flaunting them.

The band does have a breakout star, however. It’s lead singer Adam Duritz. On August, he shows himself to be a remarkable singer, songwriter, and personality. At times, Duritz is a lot like a combination between Michael Stipe and Eddie Vedder, lacking only their tiresome pretentions (sic).

Okay kid, that’s enough out of you.

After that, I took a 17-year break from Counting Crows pieces, finally re-emerging on July 12, 2011 with an essay on my favorite Counting Crows album, their second, 1996’s Recovering The Satellites. It’s also the most personal piece in my CC-related oeuvre, with a heavy focus on my life at the time of the album’s release. Weirdly, this was published exactly one year before my first child was born. Perhaps that’s why it reads as somewhat adolescent-coded to me, though not in a bad way, really.

Recovering The Satellites was released on October 14, 1996, which was about a month into my first semester at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire. I was living on the top floor of 10-story Towers North, the same dorm Justin Vernon sings about on the new Bon Iver record. [This was Bon Iver Bon Iver — ed.] This makes Towers seem a lot more romantic in my mind’s eye than it was at the time; truthfully, I was sort of miserable there. Unlike seemingly every other dude on my floor, I had never drank or done drugs at that point, and was terrified to experiment. This pretty much alienated me from all my neighbors, especially the guy next door who played Pantera’s Vulgar Display Of Power every day at exactly 3 p.m. while the two nice-enough country boys across the hall put away the better part of a Natural Ice 30-pack.

I liked Eau Claire, but it was a weird place. If I had to sum up Eau Claire’s weirdness in one sentence, it would be this: “It’s a landlocked northwestern Wisconsin town with its own water ski team.” (They’re called the Ski Sprites, and they’re technically from nearby Altoona, but you catch my drift.) But I was three hours away from home, and all of my friends were away at other schools, so any place would have been strange and uninviting.

I spent a lot of time listening to music that semester, and the albums I played the most were Weezer’s Pinkerton and Recovering The Satellites. I didn’t notice it at the time, but they’re basically the same record. Both are concept albums about going on the road and fucking up your relationships, and learning to live with that. This was something (I guess) I could relate to: I wasn’t on tour with a rock band, but I was, in a sense, “on the road” and away from my old life.

The things that fascinated Rivers Cuomo and Adam Duritz about the new reality they suddenly had foisted on them seemed a lot like what I was struggling with in my new reality—the constant sense of dislocation, the feeling that your friends and loved ones were slipping away, the self-awareness that you were presently between the identity you had shed and a new self that hadn’t revealed itself yet, and the sneaking suspicion that this dramatic change of life hadn’t erased your old fears and weaknesses like you hoped it would.

In truth, I had little in common with these guys. Maybe 20 percent of Pinkerton and Satellites actually applied in any real way to my life. But without even realizing it, I simply zeroed in on that 20 percent and disregarded the rest, which made the whole thing seem like it was about me. This is probably a common attribute of the relationships most of us have with the music we love. Which is why vague, impressionistic, non-specific lyrics are generally the best. All it takes is one song (or even one line) to speak to you in some small but incisive way, and you’ll fill in the rest with your own experience.

The following year, I interviewed the man himself, Mr. Adam Duritz, for The A.V. Club. It was intense but good. (My second interview, for my old podcast Celebration Rock, was more chill, which you can hear above.) In 2012, he was promoting the band’s new covers album, Underwater Sunshine (Or What We Did on Our Summer Vacation), but most of our talk concerned his fragile mental health, a topic he was just starting to discuss with more frankness publicly. (I quoted from those parts of the interview in my Ringer piece.)

We also talked about the thing I just quoted from that Recovering The Satellites essay, about how his “rock stardom” record was relatable for me, a non-rock star. I thought his answer was insightful:

I think the people who are able to do that, Recovering is their favorite record of ours. I think it’s just one of those attitude things that gets people to take the other side of the equation. It’s so silly. The weird thing to me is people ask me how I feel about people relating to my songs, and I just don’t know how to feel about it because when I started out I was pretty sure we weren’t going to be a very popular band. Because our songs were so personal that I didn’t think anybody else would relate to it. I thought that it was really good music; I just didn’t think it was music for everybody. I was wrong about that. I realized that fairly quickly. Actually making songs really personal and really being intimate about them is what people relate to. They find all kind of things about themselves in those songs. I don’t understand it. I do know that it’s true. People were talking at the beginning to stop using proper names, stop using particular places and details in your songwriting because people aren’t going to relate to that. But they’re wrong. Those details give those things truth, some sort of real weight.

The year after that — I was an annual Counting Crows thinkpiecer in this era, despite minimal demand — I wrote my most infamous Counting Crows essay. This one went viral, mostly for stupid reasons related to a mildly clickbait-y headline about Counting Crows relative importance to Nirvana that millions of people chose to willfully misread. It also lead, more or less directly, to me meeting my current literary agent, which was indisputably good for my life and career. So … thank you Adam Durtiz!

I quote from this one pretty extensively in the Ringer piece, as the section about “Anna Begins” sums up my whole theory on the band. It explains why I (and maybe you) love Counting Crows, and why other people have decided that they hate Counting Crows. I’ll quote it again here (with a slightly longer excerpt):

My point is that we’ve chosen to remember Counting Crows as being more different from Nirvana than it really was in 1993. Both bands were signed to the same label, Geffen. (They even had the same A&R guy, Gary Gersh.) They were both known primarily for songs (“Mr. Jones” and “Smells Like Teen Spirit”) that commented ironically on the entertainment industry. August and Nirvana’s Geffen debut, Nevermind, were both pop-oriented smashes that led to noisier, angrier, and less successful follow-ups. The no. 2 tracks on August (“Omaha”) and Nevermind (“In Bloom”) are set in unforgiving rural environments; the no. 8 tracks (“Sullivan Street” on August, “Drain You” on Nevermind) are about romantic breakups. Both bands were fronted by singer-songwriters known for their struggles with mental illness and love lives that unfolded in the tabloids. The difference is that Kurt Cobain is now an eternally romanticized dead person, while Adam Duritz exists among the eternally awkward living.

If you’re a songwriter who’s known primarily for writing sad or even downright depressing songs, you typically fall into one of two camps. The first is preferable, and it’s reserved for the “tangentially” sad. “All Apologies” is a tangentially sad song. The subject matter isn’t necessarily morose — Cobain dedicated “All Apologies” to Courtney Love and Frances Bean, which suggests that he associated the song with his attempt to find an oasis of peace in his life. But it’s impossible to hear “All Apologies” now and not think about Cobain’s death. Like much of In Utero and the entirety of MTV Unplugged in New York, “All Apologies” now seems to be exclusively about the events that led up to his suicide. It’s a sad song because of how it relates to the person who created it and the tragedy that eventually befell him — this is also true for songs by Nick Drake, Joy Division, and Jeff Buckley, among others.

The second camp is a lot less glamorous — it’s just realistically sad. “Anna Begins” by Counting Crows is an example of a realistically sad song. It describes a scenario that occurs in nearly everyone’s life at least once (if you’re lucky) between the ages of 16 and 23: A person falls in love with a friend, the friend is interested in possibly reciprocating, they consummate their feelings, it doesn’t work, and the relationship is ruined. The song is so direct and plainspoken that it hardly seems like art;11 it just sounds like dialogue that’s been transcribed from a million arguments between emotionally exhausted parties:

It does not bother me to say this isn’t love

Because if you don’t want to talk about it then it isn’t love

And I guess I’m going to have to live with that

But I’m sure there’s something in a shade of gray

Or something in between

And I can always change my name if that’s what you meanI don’t know if I ever said those exact words to a woman, but I’ve said something like those words. And hearing Duritz sing them never fails to make me cringe a bit. Not because it makes me think about Duritz and the circumstances of his life, but because it makes me think about my life, and not a particularly good part of my life. This is Duritz’s unique talent as a songwriter: He vividly re-creates the feeling of your lowest of personal lows — the “it’s 4:30 a.m. on a Tuesday and it doesn’t get much worse than this” moments that many of us would just as soon forget.

The last Counting Crows essay I wrote (before the current one, and whichever Counting Crows opus I’m convinced to write in a year or two) came out in 2021 but it’s especially timely right now: It’s about how “A Long December” is a great holiday song. My argument is, of course, long and convoluted. But it’s pretty much summed up here:

As we’ve established, this tune is a series of not-quite-connected scenes that allude to the real-life story about the friend in the hospital, Duritz’s feelings about fame, and a mystery woman who might in fact be a metaphor for unrequited longing. But when you add up all those elements, it somehow transforms into a song about how the holidays send us down the wormhole of our own pasts in search of a version of ourselves — or our parents, or high school friends, or our hometowns — that no longer exists. The “festive” mood always has loss and melancholy baked in.

But if “A Long December” is about how the constant churn of the holidays can make you sad, it’s also about how surviving the holidays can make you hopeful about what lies beyond them. It’s both an acknowledgement that, yes, it’s right that you feel depressed right now and also a pat on the back that, [heavy sigh], you have survived it for yet another year. A simultaneous wallow and pep talk — that’s “A Long December,” and that’s why it’s the best holiday song. Hold on to these moments as they pass. You deserve it.

And there you have it. Counting Crows is a band that’s meaningful to me because they were meaningful to me when I was young, yes, I admit that. But (as I argue in The Ringer piece) I also think Duritz is a savant of heartland rock, whose talent for writing (often embarrassingly) emotional songs derived from the canon of rootsy, vision questy guitar music (spanning The Basement Tapes, Born To Run, The Joshua Tree and Automatic For The People) blossomed at possibly the worst moment for that kind of music in modern popular music history. And he’s taken a lot of shit for that. (And the dreadlocks. Can’t forget the dreadlocks.) But that’s not his fault, it’s ours.

So much awesomeness to delve into in here. HOWEVER, I shall never forgive you for not including "Mrs. Potter's Lullaby".

I've always thought Adam Duritz would be the ideal twink sub for Vladimir Putin as the dom in some gay BDSM porn.

But only because . . .

[snap][snap] Putin on Duritz.