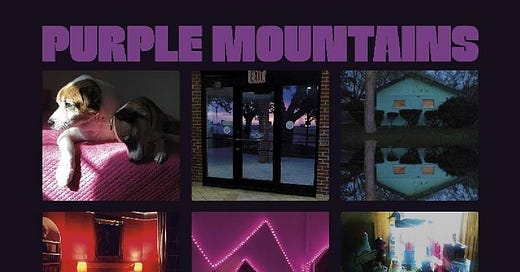

On "Purple Mountains," 5 Years Later

Revisiting One Of The Greatest (And Most Painful) Albums Of Recent Times

Five years ago this month, I was supposed to see David Berman play live. The tour in support of Purple Mountains, Berman’s triumphant and critically adored comeback after a decade-long hiatus, was to begin on Aug. 10, and he was due to play my area 13 days later. Even better, at the conclusion of an interview I conducted with Berman that June, we planned to meet up at the show. I couldn’t have been more excited. And Berman, he told me, felt likewise. “I can’t wait,” he said of the tour before we hung up the phone. “I’m ready for my solitude to end.”

Of course, we all know what happened after that. Some time on or around Aug. 7, David Berman hung himself in a Park Slope apartment. He was four days into rehearsals for the tour, in which he would have been backed by members of Woods, as he was on the record. He was 52 years old.

When I heard Berman had died, I was perhaps more surprised than most. He had done a round of interviews ahead of the album release, and many of the profiles struck an ominous tone about his mental state. But I actually felt positive about our 90-minute interview. He seemed genuinely enthusiastic about touring despite his decided lack of interest in playing live in the past. And then there was our email correspondence, which began in January of 2019 when he reached out, to my great surprise, after seeing some tweets I had made about Silver Jews’ masterful 1998 record American Water. “More often than I’d like to admit I search Twitter for ‘Silver Jews,’ looking for a shot of courage, lurking for a good sign,” he wrote. “And more than once you were my signal to keep going. A few critics like a few albums but you’re the only writer I’ve read that takes it as a given that the music is good.”

I couldn’t tell if he was buttering me up or if he genuinely believed that I was one of the only music critics “that takes it as a given that the music is good.” Because that obviously was not true. Berman never achieved mass stardom (or even significant indie fame), but there were plenty of music writers (as well as musicians) who properly revered him as the best lyricist of his generation. His retreat from music had only extended his mythic status.

Berman further flattered me when he mentioned that he had checked out my book Twilight Of The Gods. He mentioned a chapter I had written about the conclusion of the classic rock era, which I put at the end of the nineties. And then he attached a graph charting the decline of classic rock and the corresponding arcs for ketchup and catsup. Clearly, he was fucking with me. Either way, it made me laugh.

More important, he slipped me a download link for a 44-minute MP3 of the Purple Mountains record. Whether my accident or design, I was forced to play the 10-song album as a single statement of purposeful despondency. I wrote him back the next day and told him I thought the record was “beautiful, funny, and sad.” I particularly liked the line where he sang, “I want to be tantamount to cordial,” as I find myself struggling to be tantamount to cordial in my own life. But I also marveled at how perfectly worded that lyric — and seemingly every other line on the record — was. You know a line is well crafted when it instantly sticks in your head like a good musical hook does. And Purple Mountains has countless lines like that. I raved about about other lyrics that had already lodged themselves in my brain: “I spent a decade playing chicken with oblivion’; "We’re drinking margaritas at the mall”; “Snow is falling in Manhattan in a slow diagonal fashion.” Berman had worked on these songs for years and it showed.

At that point, I heard Purple Mountains as a set of songs by a depressed and lonely man determined to reenter the world, because that was how Berman had approached me. A man with a death wish doesn’t work this hard. A person with no hope doesn’t make a concerted effort to reach out. A guy at the end of his rope doesn’t spend 10 years in the wilderness, finally win back public adoration, and then end it. Right? Right?

When Berman killed himself, I was gobsmacked. Five years later, I still don’t get it. I don’t think I’ll understand it 50 years from now. But that’s how these things go.

The album that Berman put out one month before he took his own life will forever be defined by the tragic post-release circumstances. This is understandable, though it also bothers me. Yes, Purple Mountains is the most emotionally painful capital-M “masterpiece” of the last 10 years. The songs are obsessed with death and regret and express a view of the universe that is cold and unforgiving. But the common perception of Purple Mountains as a musical suicide note flattens the album, and disregards its myriad moments of grace. I feel now as I did then: This record is beautiful, funny, and sad — though not necessarily in that order.

But I do want to stress the “funny” part. Berman’s way with words was inherently witty, even when those words were conveying self-annihilating impulses. The sentiment of “If no one is fond of fucking me / maybe no one’s fucking fond of me” might be despairing, but the way Berman expresses it is so clever that it reads as drolly self-effacing. Or at least it read that way before. Now, the reflexive response is to only hear the despair.

Again: I feel like this reduces a great work of art. I would rather think of Purple Mountains as an indie-rock All That Jazz, a tragic-comic excursion into a troubled genius’ psyche as he lingers on the precipice of a bottomless void. It’s the sound of man trying to process his demons, or at least keep them at bay for 44 minutes. Because songwriting for Berman was ultimately an expression of life, not death. He’s fighting to stay alive on Purple Mountains, and the effort is courageous and valiant. “I don’t have religion or culture. I don’t have anything I can believe in when I’m really scared,” he told me. “When I play the songs, I feel the fear disappear.”

The song from Purple Mountains that moves me the most also epitomizes the album’s duality on mortality. “Nights That Won’t Happen” opens with a lyric that those inclined to hear Purple Mountains as a forensic explanation for Berman’s death latched upon: “The dead know what they're doing when they leave this world behind.” Even before Berman’s suicide, the line immediately stood out. “It’s kind of an angry thing to say,” Berman admitted when I asked him about it. “It can be seen as a positive. It could be something reassuring you’d say to a child, but it can also be said with incredible bitterness.”

After Berman died, it only sounded bitter. But when he wrote “Nights That Won’t Happen,” I suspect he was thinking of his beloved mother, whose death inspired him to start writing songs again. (The unbearably poignant “I Loved Being My Mother’s Son” is the most explicit song about this subject.) In that context, the “something reassuring you’d say to a child” part rings true, particularly when you imagine Berman addressing his own grieving inner child.

I find the words to “Nights That Won’t Happen” to be positively breathtaking. I want to pull out memorable lines, but I would end up quoting the entire song. But this verse has haunted me for years:

And as much as we might like to seize the reel and hit rewind

Or quicken our pursuit of what we're guaranteed to find

When the dying's finally done and the suffering subsides

All the suffering gets done by the ones we leave behind

The boy sang this about his mother to feel better about her moving on. And now I play it to feel better about the boy who wrote it moving on.

Self Promotion Time

For Uproxx I wrote about my favorite AC/DC songs, because it’s the middle of summer and I like to listen to AC/DC in the middle of summer.

I am doing a book event in Minneapolis at Magers & Quinn with my pal Alex Pickett on Aug. 8. If you’re in the area, please come through! Admission is free, though they ask that you register ahead of time here.

It's a beautiful record but hard to listen to. Every time someone asked DCB how he could write so many clever lines in his lyrics and he would respond with something like "I wrote 99 less clever versions first--you're seeing only the best one." He made it clear that his genius didn't fall from the sky, that he had to work at it. Which is a useful thing to hear for those of us who feel less talented.

Purple Mountains belongs nowhere near the patio hall of fame. Maybe it should be the first entry in the dark basement hall of fame instead.

This is a gorgeous piece about a beautiful record. Thanks for writing it, Steve.

I loved this quote:

"Because songwriting for Berman was ultimately an expression of life, not death. He’s fighting to stay alive on Purple Mountains, and the effort is courageous and valiant. 'I don’t have religion or culture. I don’t have anything I can believe in when I’m really scared,' he told me. 'When I play the songs, I feel the fear disappear.'"

I had to take a few years off from the record after his death and only returned to it this summer. When I did, I was overcome by how well crafted it is. "I Loved Being My Mother's Son" -> "Nights That Won't Happen" is some of the best music ever made, and the LP as a whole is truly one of the best records of the last several decades easily. That said, I am glad that I first was able to hear it in that liminal period post-release but before his passing in summer 2019. It really felt celebratory in a way that is hard to imagine myself back to now. But I took solace this summer when I revisited the record in just how beautifully rendered it all is.