How Listening To Jam Bands Revived Me

Plus: A rare audio interview with Cass McCombs and thoughts on Ethel Cain

As I hinted in the previous newsletter, I saw Billy Strings live for the first time last weekend and came away very impressed. I wrote a column about it, which was an excuse to also reflect on my dozen years in the jam-band wilds as a writer and fan. The journey unofficially started in 2013 with a Grantland column about Phish, which marked my public coming out as a jam guy. I tried to explain the broader ways this impacted my life as a critic and listener.

My interest in this stuff was sparked by two forces, one cultural and one personal. This might be hard to appreciate now, but in 2013, it really did seem like recorded music might be in the midst of an extended and inexorable decline. Not that I thought that it would go extinct outright, exactly. But in that window of time between the proliferation of online piracy in the aughts and the rise and dominance of streaming that took hold in the late 2010s, you could envision a different paradigm potentially arising. “Live music endures — it can’t be mass-produced, diluted, or ‘shared’ in a digital realm,” I wrote. “If artists no longer have the means to make records, the concert stage will become their primary canvas.” And in that paradigm, I reasoned, it was very much worth taking Phish seriously, given how they “presented an alternative model in which memorable live experiences mean at least as much as iconic songs, and high-grossing tours measure an artist’s reach as well as chart-topping albums do.”

That was the broader cultural force pushing me to jam bands. Meanwhile, on a personal level, I was a music critic in my mid-30s, and I was feeling a little burned out — mostly by the churn of cyclical discourse and the media apparatus propagating it. This was amid poptimism’s hostile takeover of music writing, when on any given day you might see the critic for the New Yorker publicly challenging a thinkpiecer from Salon.com to a public duel over his allegedly offensive criticism of Taylor Swift, triggering a massive and tiresome social-media pile-on. I started to look over the fence at a lustrous green lawn populated by musicians and fans ignored by most music writers. This is slightly less true now, but back then jam bands were deemed unworthy of any even passing critical consideration, a sign of disrespect that was actually an accidental blessing. That world was below the media’s radar, but to my eyes, it was above the fray. I imagined it as a mini utopia where people simply “liked music for the music.” Sounds corny, I know, but it was preferable to being hammered by a theoretical agenda expressed in increasingly hectoring and annoying fashion. Liking Phish was about as far away from that caterwauling circus as you could get.

Now, clearly, I was wrong about a lot of that, though I wasn’t completely wrong. Recorded music is still very much a thing, obviously, but it’s also true that live music is more important than ever — “being good live,” as it were, has gone from being a driver of record sales to the cornerstone of most performers’ livelihoods. Ultimately, I think it’s fair to conclude that, in 2025, “memorable live experiences mean at least as much as iconic songs” and “high-grossing tours measure an artist’s reach as well as chart-topping albums do,” if not more so.

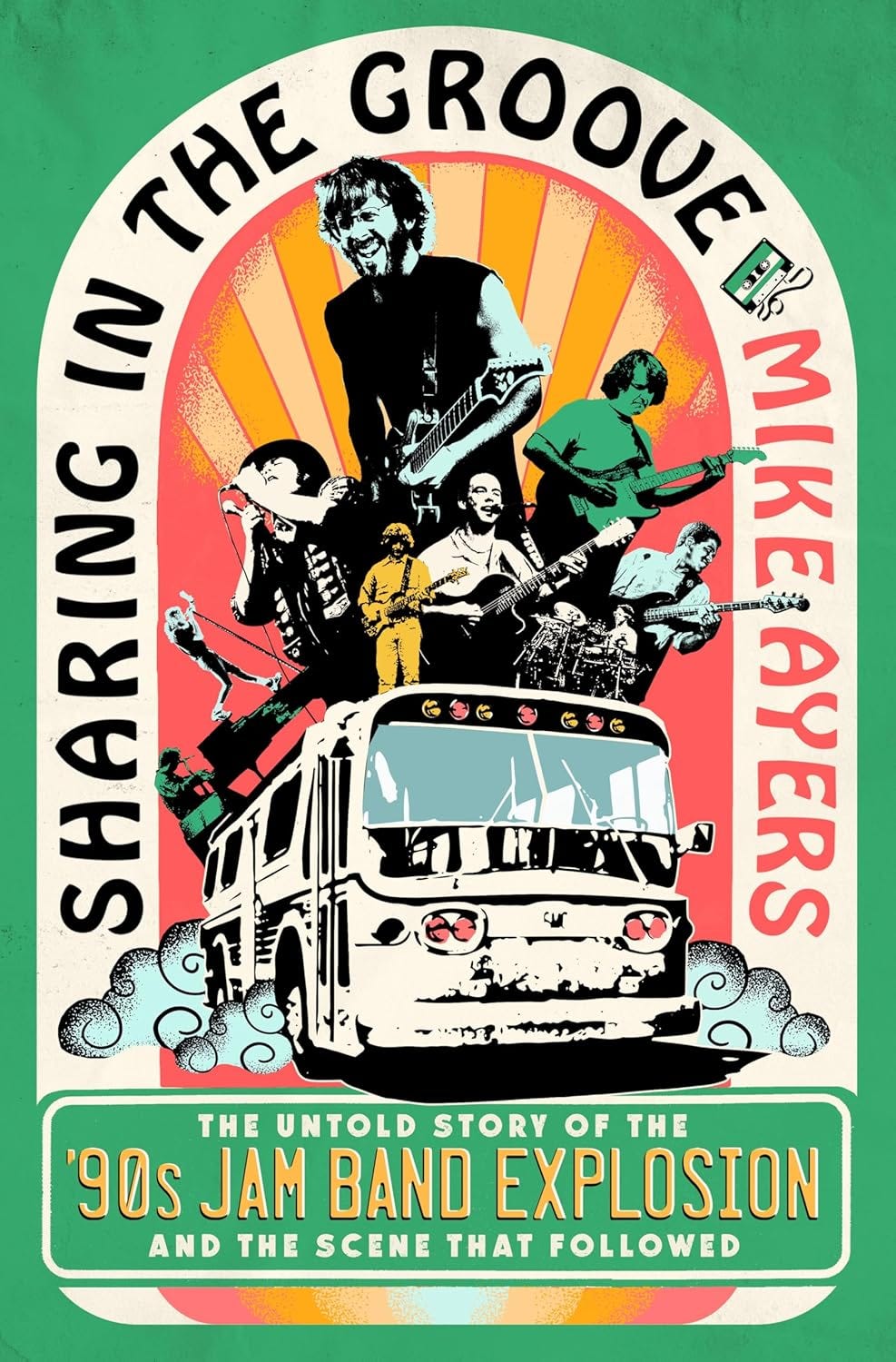

As for me, making the decision to interact deeply with jam-band culture transformed me in a number of ways, starting with my status as a kind of “jam guy” pundit. I hosted a popular Grateful Dead podcast for a few years and I occasionally write articles that annoy people on Reddit. (You can also see my blurb on the back cover of this excellent recent oral history of ’90s jam-band culture.) But more than that, listening to the Dead and Phish changed how I listen to all music, no matter the proximity to jamminess. In my spare time, I probably listen to bootleg recordings more than proper albums, by a wide range of artists. And I’m much more likely to factor in those listens into my overall assessments of those acts as I am their “official” releases. (I don’t think I would be co-hosting a podcast on Bob Dylan’s “Never Ending Tour” if hadn’t written that Phish column.)

Here’s another tangible way that listening to jam bands affected my writing: My 2020 book about Kid A includes a ton of material about Radiohead’s progression as a live band. The discussion of bootlegs extends directly from jam bands, in essence, training me to take the live experience as seriously as the albums. (This approach also informed my Pearl Jam book to an even greater degree.) Anyway, I bring this up because Radiohead just released a live compilation of songs from the Hail To The Thief era. Now, the jam band purist in me would have preferred a complete show to a comp, but nevertheless the performances here are uniformly outstanding.

In that column excerpt, I reference a new oral history book called Sharing In The Groove: The Untold Story of the '90s Jam Band Explosion and the Scene That Followed by Mike Ayers. Mike was kind enough to share an advance copy a while back, and I ended up blurbing it. Here’s what I said: "The jam band world is a bit like Fight Club ― it's something we all know exists, but are not supposed to talk about. That is, until now. Mike Ayers has done the work of shining some light on a woefully under-covered corner of modern music. In the process, he finds the kinds of stories that even the most ardent tape collectors haven't heard before." Sounds like a good book to me! If you’re at all interested in this sort of thing, I suggest checking it out!

Over at Never Ending Stories, we took a short break from chatting about Bob Dylan and instead interviewed the great singer-songwriter Cass McCombs, who just released yet another great album, Live Interior Oak. Cass belongs in that lane of enigmatic indie lifers (with people like Dan Bejar and Bill Callahan) who are have so consistently good for so long that they inevitably get taken for granted. Cass is probably a little less famous than those other guys, because he’s also more enigmatic. He has a reputation for not doing a lot of press, though if you Google him (and pry past the AI garbage at the top of the search) he does have a fair number of interviews. (I last talked to him in 2019.) However, he doesn’t share a whole lot in those sit downs, preferring an old-school, “close to the vest” approach. I respect that, though I also appreciated how he opened a bit more on our podcast. (We also solicited input from peers and admirers like Matt Sweeney, Blake Mills, and Ryley Walker.)

Finally, I wrote a bit about Ethel Cain, whose latest album Willoughby Tucker, I'll Always Love You is a fascinating and frustrating listen. This opinion apparently pissed off a lot of people on Instagram, where the column went semi-viral. I’ll let you decide whether I’m off-base here or not.

Hayden Anhëdonia is a master mythologist. As the creator of Ethel Cain, pop music’s reigning undead goth princess, she signaled a vibe shift away from the nonstop millennial moralism of the Trump 1.0 era and toward something darker, sicker, and more immersive. Her 2022 debut Preacher’s Daughter is one of the decade’s genuine left-field hits — possibly the pop cult success of the 2020s, so long as Chappell Roan no longer counts as a cult hero — and the single “American Teenager” remains a stirringly subversive spin on post-Taylor Swift coming-of-age anthems. In an era where “empowerment” and “trauma” became overused buzzwords in album PR announcements, Anhëdonia stood out with songs drenched in cannibalism, murder, and sexual perversity, among other transgressions.

There are, however, limits to her virtuosic prowess for spinning beautiful BS. For instance: In a recent interview, Anhëdonia claimed that she watched Twin Peaks while making her new album, Willoughby Tucker, I’ll Always Love You. Nothing surprising about that — few musicians of her generation are better suited for the adjective “Lynchian” than Anhëdonia. However, she insisted that this was her first time watching the iconic television series. And, I’m sorry, but even in the fanciful world of Ethel Cain, that statement strains credulity. It would be like if Quentin Tarantino declared that he caught his first Scorsese movie just last week.

Then again, it’s possible that Anhëdonia hasn’t studied Twin Peaks as closely as I assume. Along with co-creator Mark Frost, David Lynch pulled off two very different feats with that show. On one hand, he crafted something wholly unlike anything on television, a meditation on moral corruption and small-town secrecy that indulged fearlessly in atmospheric and semi-subliminal visual abstractions. On the other hand, Twin Peaks also worked as conventionally satisfying television, with well-written characters and a compelling mystery that captured the cultural zeitgeist. To make a musical analogy: Twin Peaks functioned as both an experimental ambient record and an easily accessible pop tune.

Then again, it’s possible that Anhëdonia hasn’t studied Twin Peaks as closely as I assume. Along with co-creator Mark Frost, David Lynch pulled off two very different feats with that show. On one hand, he crafted something wholly unlike anything on television, a meditation on moral corruption and small-town secrecy that indulged fearlessly in atmospheric and semi-subliminal visual abstractions. On the other hand, Twin Peaks also worked as conventionally satisfying television, with well-written characters and a compelling mystery that captured the cultural zeitgeist. To make a musical analogy: Twin Peaks functioned as both an experimental ambient record and an easily accessible pop tune.

While those songs were used as teasers to draw listeners to Willoughby Tucker, they aren’t really representative of the overall record. “Dust Bowl” is more indicative — a glacially paced mood piece trained on a sadomasochistic relationship dynamic (“I knew it was love / When I rode home crying / Thinking of you fucking other girls”), it’s noticeably stingy when it comes to dishing out dynamic musical morsels. It unfolds largely as an unchanging block of sound, where the appearance of a distorted guitar riff at the song’s midpoint feels like a drop of water in an arid desert. It hits hard, but it’s not enough.

I am officially looking forward to your newsletter each week!

I was at a brewery last night hosting live music, and I wore my Billy Strings T-shirt I picked up at the Minneapolis show, and at least five people paused to chat about their love of Billy. I am pretty sure that, last summer, no one would have said anything. I have seen him 3 times over 3 years, and the venue has doubled in size each time. I am shocked that a bluegrass jam band hybrid like this is gaining traction. Gate receipts and merch sales are the new charts!